%20copy%20(1).png)

A stock market crash is a sudden and severe decline in stock prices across a broad index, often by 30 per cent within days. These events are usually triggered by speculative bubbles, economic crises, or external shocks. Panic selling accelerates the fall, pushing markets into deeper decline.

Quick summary

- Definition: A crash is a rapid, double-digit market drop within days, usually fuelled by panic, speculation, or external shocks.

- Historical crashes: the 1929 Great Depression, Black Monday 1987, the dot-com bubble 2000–01, the global financial crisis 2008, and the COVID-19 pandemic 2020.

- Main causes: Speculation, excessive leverage, inflation and interest rates, political instability, and black swan events.

- Impact: Destruction of wealth, recessions, job losses, bankruptcies, and shifts in investor behaviour.

- Trading opportunities: Volatility strategies, short selling, and safe-haven flows.

Examples of historical market crashes

The great depression (1929)

In 1929, widespread speculation and margin buying pushed U.S. stock prices far beyond fundamentals. When confidence broke, panic selling swept through markets, triggering a collapse that ushered in the Great Depression and reshaped the global economy.

Black Monday (1987)

On 19 October 1987, U.S. markets fell over 20% in a single day. Computerised trading systems amplified the speed of the decline, turning fear into a full-scale crash. Despite the severity, markets recovered faster than in 1929, though the event reshaped how regulators approached volatility.

The Dot-Com bubble (2000–2001)

The late 1990s saw a frenzy of investment in internet start-ups, many of which had little more than a business plan. As these firms ran out of capital, tech-heavy indexes collapsed. Billions in investor wealth evaporated, but the crash also paved the way for stronger technology companies to dominate in the years that followed.

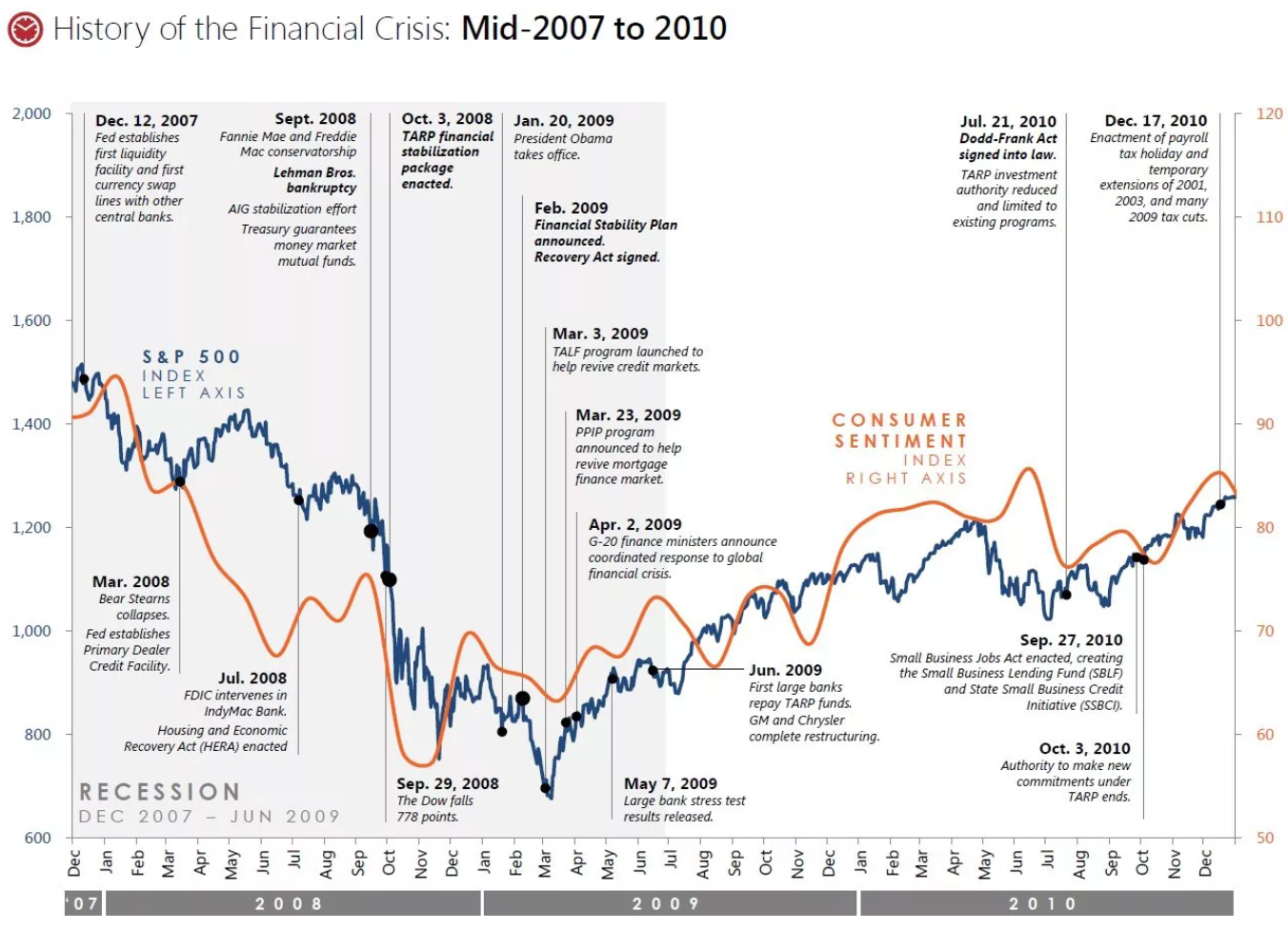

The global financial crisis (2008)

The housing boom and the rise of mortgage-backed securities created dangerous leverage across the banking system. When homeowners began defaulting, financial institutions collapsed under the weight of toxic assets. The crash triggered the Great Recession, one of the most severe economic downturns in modern history.

The COVID-19 pandemic crash (2020)

Global lockdowns and the shock of a fast-spreading virus caused one of the sharpest downturns in history. In March 2020, stock markets plunged into bear territory within weeks. Trading halts, known as circuit breakers, were triggered multiple times on U.S. exchanges as fear swept across global markets.

Causes of stock market crashes

Speculation and market bubbles

Many crashes begin with a period of speculative excess. In 1929, overconfidence inflated stock valuations; in 2000, the dot-com boom pushed tech stocks to unsustainable highs. When fundamentals reassert themselves, bubbles burst.

Excessive leverage

Borrowing magnifies gains when markets rise but destroys capital when they fall. Investors who buy heavily on margin are forced to liquidate during downturns, driving prices even lower. Leverage played a central role in both the 1929 crash and the 2008 financial crisis.

Inflation and rising interest rates

When borrowing costs rise, consumer spending and business investment slow. Equities, which thrive in expansionary conditions, come under pressure. Prolonged inflation and tightening central bank policy often set the stage for declines.

Political and geopolitical risk

Markets favour stability. Wars, political turmoil, and abrupt policy shifts undermine investor confidence. Uncertainty over trade wars, military conflicts, or sudden tax changes can trigger sharp sell-offs.

Black swan events

Sometimes, the cause is entirely unexpected. Natural disasters, pandemics, and terrorist attacks disrupt economies with no warning. The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic is the clearest recent example of how an external shock can plunge global markets into chaos.

Impact of stock market crashes on markets and traders

1. Wealth destruction

Market crashes can wipe out years of accumulated wealth within days. Stock portfolios, pension funds, and even real estate values can fall sharply. For retail investors, this often leads to panic selling, locking in losses rather than waiting for recovery.

2. Credit tightening and investment slowdown

Companies suddenly face higher borrowing costs as banks become risk-averse. Access to capital dries up, expansion plans stall, and innovation slows. This credit squeeze amplifies the downturn as businesses reduce investment.

3. Recessionary effects

When investment declines, the knock-on effects are brutal—layoffs, reduced consumer spending, bankruptcies, and, in extreme cases, systemic financial crises. These conditions often result in recessions, with ripple effects across global supply chains.

4. Opportunities for traders

Paradoxically, periods of extreme volatility offer fertile ground for prepared traders. Safe-haven assets like gold and government bonds attract inflows, while short-term strategies (like swing trades or volatility plays) can generate profits. Traders who remain calm and adapt can turn chaos into opportunity.

Market volatility and trading opportunities during market crashes

Volatility describes the speed and intensity of price changes. During crashes, it spikes sharply. Traders can adapt through breakout strategies that capitalise on new price levels, mean reversion approaches that bet on returns to averages, or momentum strategies that ride strong trends. For more advanced traders, instruments like options, volatility indices, and CFDs provide direct exposure to price swings.

How to make stock market crashes potentially work in your favour

Short selling

How it works:

Traders borrow an asset (like a stock) from a broker and sell it immediately, hoping its price drops. Later, they buy it back at the lower price and return it, pocketing the difference.

Imagine you borrow your neighbour’s bike because you think its value will fall.

- You immediately sell the bike for $200.

- A month later, the bike’s market value drops to $120.

- You buy it back at $120 and return the bike to your neighbour.

- Your profit = $80 (minus borrowing fees).

That’s essentially what short selling is: profiting from a fall in price by selling first and buying later.

Historical analogy: The great depression (1929)

In the lead-up to the Wall Street Crash of 1929, many traders engaged in short selling as stock prices began to wobble. When panic selling hit, short sellers made enormous profits by buying back shares at fire-sale prices.

However, their actions also made the crash worse—prices fell even faster as short selling piled on the pressure. This led regulators later to impose rules (like the “uptick rule”) to prevent short sellers from accelerating market collapses.

- Why it matters in volatility

Market downturns can be sharp and fast. Short selling allows traders to profit from falling prices instead of sitting on losses.

- Risks: If the price rises instead of falls, losses can be unlimited; a short seller may have to buy back at much higher levels. That’s why short selling is often paired with strict stop-losses or hedging strategies.

- Example: During the 2008 financial crisis, hedge funds that shorted financial stocks made massive gains as banks collapsed.

Safe-haven assets

When fear grips markets, money tends to flow into assets that investors trust to preserve value. These are less about making quick profits and more about shielding capital from chaos.

Classic safe havens

- Gold: Seen as a timeless store of value, especially during inflation, currency weakness, or geopolitical stress.

- U.S. Treasuries: Backed by the U.S. government, they’re considered the “world’s safest” fixed-income instrument. Prices usually rise (yields fall) when investors flee risk.

- Currencies:

- U.S. Dollar (USD): Dominates global trade and finance; demand surges in crises.

- Japanese Yen (JPY): Historically benefits when global risk appetite vanishes.

- Swiss Franc (CHF): Stability and Switzerland’s financial system make it a safe-haven currency.

- U.S. Dollar (USD): Dominates global trade and finance; demand surges in crises.

Defensive stocks

- Healthcare and Consumer Staples (like food, beverages, and household products) typically hold up better in downturns. People still need medicine, groceries, and basic goods regardless of recessions.

- These aren’t risk-free but often provide relative stability compared to high-growth sectors like tech or luxury goods.

Risk management during volatile periods

Survival during a crash depends on discipline. Reducing leverage, trading smaller positions, and scaling into entries all help manage risk. Stop-losses and trailing stops remain critical but should be adjusted for wider swings. Diversification across sectors and regions cushions losses, while holding cash provides the flexibility to act quickly when new opportunities arise.

Strategies for navigating a crash

Traders should resist the urge to panic. Selling impulsively often locks in losses just before markets rebound. Focus on liquidity, keep positions manageable, and remain disciplined. Volatility can be turned into an opportunity if approached with preparation. Always remember: every major market crash in history has eventually been followed by recovery.

Stock market crashes are disruptive but also inevitable. They erase wealth and fuel fear, yet they present opportunities for those who understand their dynamics. By studying historical examples, recognising common causes, and applying disciplined risk management, traders can turn volatility to their advantage.

Ready to put these lessons into practice?

Trade global stocks with Deriv and access advanced tools to navigate volatility with confidence.

Quiz

What is "short selling" in the context of a stock market crash?